The Lados List

See below for excerpts from the book, The Lados List.

For a list of visas provided by the Lados Group, see The Lados List - Visas.

The Lados List (Excerpts)

An index of people to whom the Polish Legation and Jewish organizations in Switzerland issued Latin American passports during the Second World War

Jakub Kumoch (ed.)

Monika Maniewska

Jędrzej Uszyński

Bartłomiej Zygmunt

Translation by

Julia Niedzielko, Ian Stephenson

Pilecki Institute

Preface to the Second Edition

Reactions to the publication of the first edition of The Ładoś List exceeded expectations. The book was received by a broad audience, including Jewish circles both in Europe and the United States, who in turn furnished hitherto unknown stories of survivors and revealed new source material and documentation. After years of silence, the operation to rescue Jews carried out by Polish diplomats and Jewish activists based in the Swiss capital of Bern, has finally become a subject for international debate. Holocaust survivors and their descendants, relatives of the Ładoś Group members, historians, experts and journalists from across the globe have all become involved in the discussion; with their aid, further supplemented by numerous meetings, research at the Pilecki Institute and the inquires it makes, and the broad general interest in the topic, work on the Ładoś List continued and more and more names have been added. As a result, it has been possible to present a second, expanded edition of the publication. […]

The Ładoś Group

From at least the beginning of 1941 until the end of 1943, a group of Polish diplomats, led by Aleksander Ładoś, the Polish envoy in Bern, engaged in a remarkable venture. Cooperating with at least two Jewish organizations—the World Jewish Congress (WJC) and Agudat Yisrael (Hebrew: Union of Israel)—the group illegally purchased and issued passports and citizenship certificates of four South and Central American states: Paraguay, Honduras, Haiti and Peru. They used these documents with the intention of saving Jews during the war.

Initially, the passports and certificates were sent exclusively into German-occupied Poland. In time, they became the tool for a rescue operation which was expanded to include Belgium, the Netherlands, France, Slovakia and Italy, but also German and Austrian Jews who had been stripped of their German citizenship, as well as individual citizens of other nations. The documents significantly increased the bearers’ chances of surviving the war, as they declared them to be “foreigners”. As such, those individuals would be included on lists of Jews marked for prisoner exchange, or transported as inmates to transit camps instead of extermination camps.1[1]

The work presented here is the first attempt to create a list of the people for whom those documents were prepared. This is done without regard to whether those individuals in question were aware of the circumstances surrounding their issuance and regardless of the later fates of their bearers. These documents—both the passports and the citizenship certificates—are conventionally referred to as “Ładoś passports”, in order to differentiate them from Latin American passports forged outside Switzerland, or those issued within Switzerland but probably without significant involvement of the Polish diplomats, such as George Mantello’s Salvadoran papers.[2]

By using the names “Ładoś passports”, “Ładoś group”, or “Ładoś list”, it is assumed—and it is an assumption that has been confirmed many times by the participants of the rescue operation themselves—that the key to the success of the entire operation was the support of the Polish envoy[3] Aleksander Ładoś.[4] As the head of the Legation, Ładoś put himself and his diplomats at the disposal of his Jewish partners and gave them political protection. In addition, Ładoś led a significant part of the work along with at least three other Polish diplomats. Together, they began an effective diplomatic campaign to have the documents recognized by the authorities in whose name the documents had been issued. Witnesses at the time often recalled that the operation would not have been successful without Ładoś’s support,[5] and he was referred to by at least one of the Jewish members of the rescue operation, as “Righteous Among the Nations” (see Document 1).

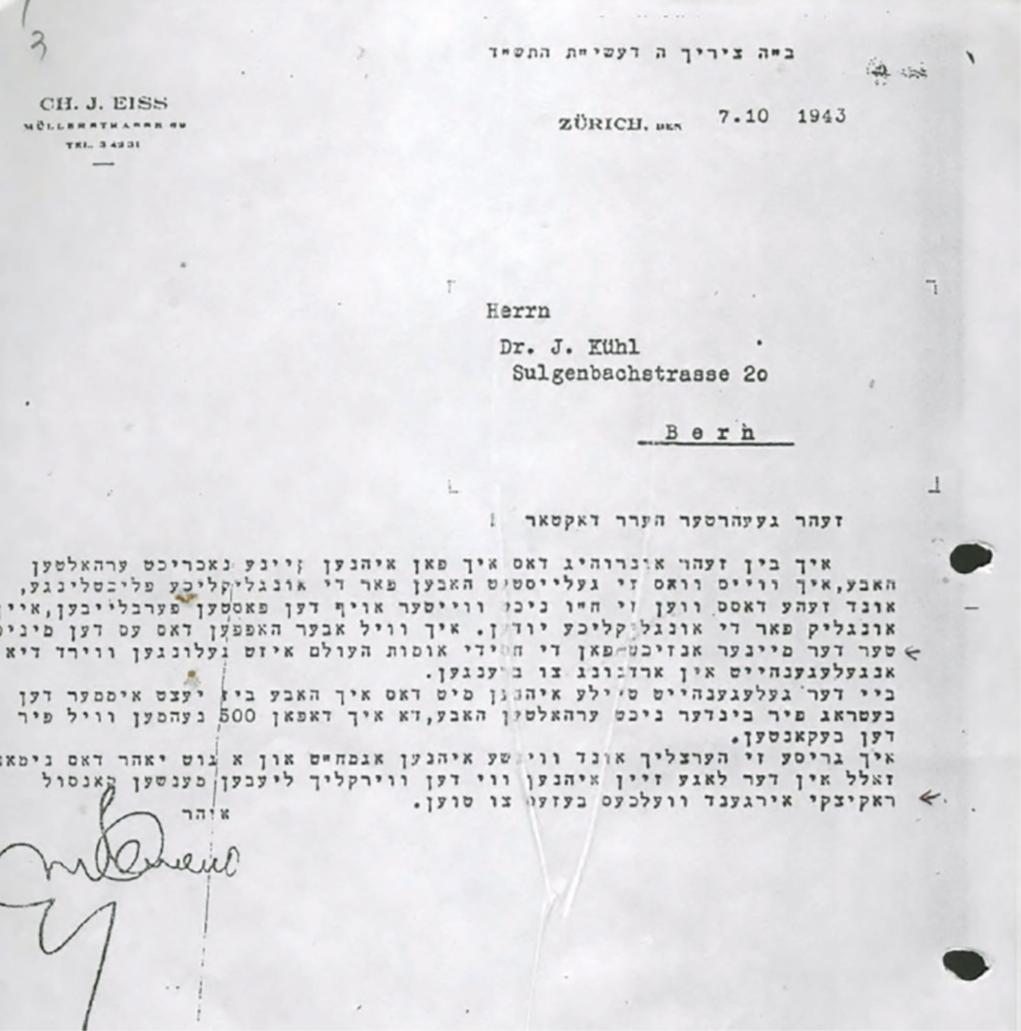

Document 1. Letter from Chaim Eiss to Juliusz Kühl dated 7 October 1943 in which he calls Aleksander Ładoś “Righteous Among the Nations” (copy currently located in the Polish Embassy in Bern, acquired from the Eiss family)

Alongside Ładoś himself, the group included the deputy head of the Legation, Stefan Ryniewicz,[6] Vice-Consul Konstanty Rokicki,[7] attaché of the Polish Legation, Juliusz Kühl,[8] and two representatives of Jewish organizations: Abraham Silberschein[9] (WJC and RELICO – Committee for Relief of the War-Stricken Jewish Population, which he had founded) and Chaim Eiss[10] (Agudat Yisrael).[11] Based on analysis of the available documentation, it is concluded that only these six members (Eiss, Kühl, Ładoś, Rokicki, Ryniewicz and Silberschein) were apprised of the whole operation and informed of the roles played by the other members. Those outside this intimate circle often knew only that Jewish organizations were trying to “arrange” Latin American documents with the unspecified “support” of the Polish Legation.

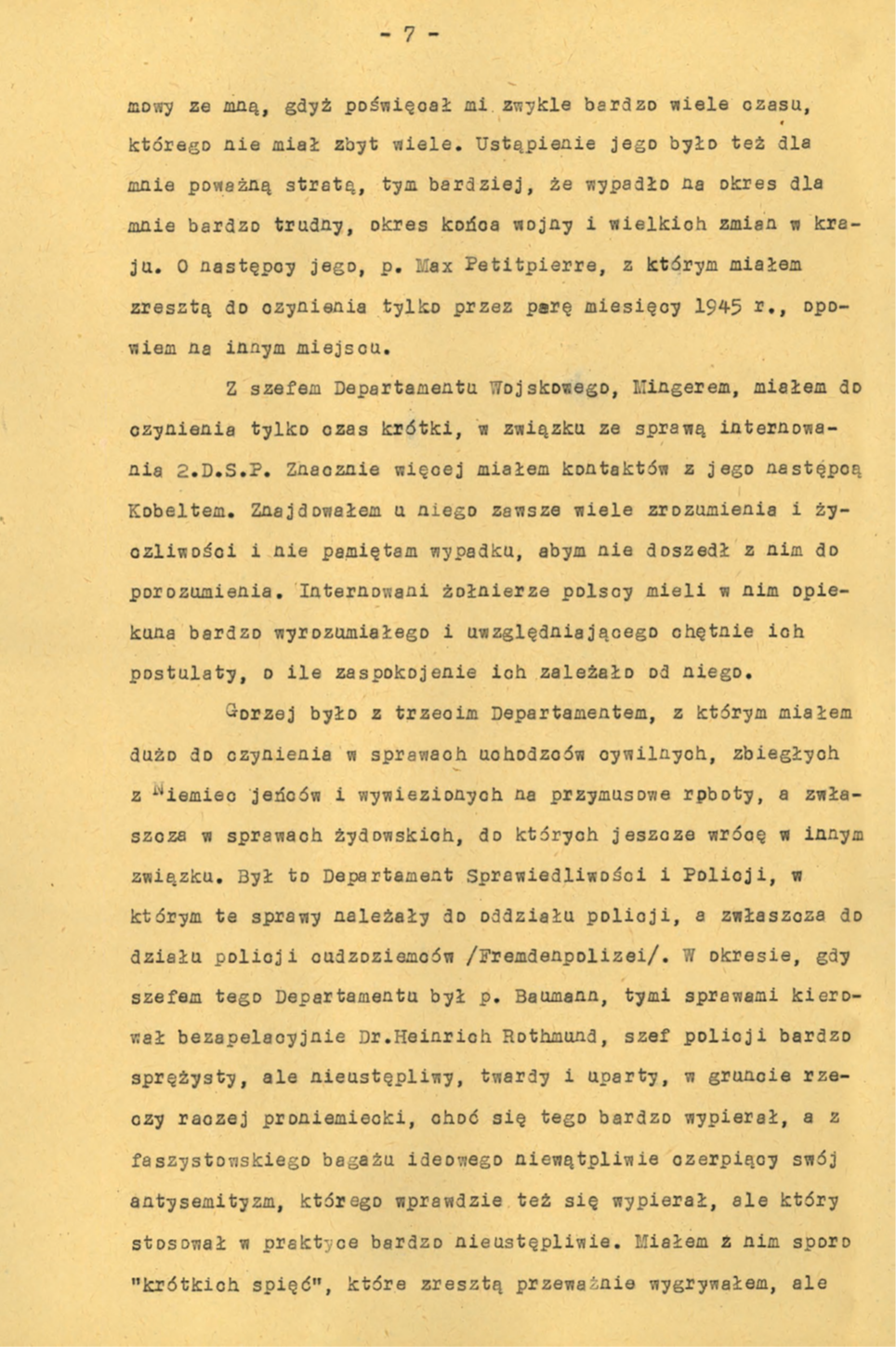

Unfortunately, none of the members left behind any completed memoirs which might clarify the process of forging. Aleksander Ładoś recalled an operational narrative “on Jewish issues” (see Document 2),[12] but he died before he could finish his memoirs. Juliusz Kühl, whose recollections were recorded in the 1970–1980s, made no mention of the passport operation.[13] No evidence of the existence of memoirs from Ryniewicz, Silberschein or Rokicki has been found, and Eiss died in October 1943 while the passport campaign was still on-going.

Document 2. Fragment of Ładoś’ unpublished memoirs in which he alludes to a detailed description of the passport issue (source: CAW, file no. WBBH IX.1.2.20, Pamiętniki A. Ładosia, vol. III, p. 7)

Broader circles of insiders knew about the passports as a means of saving lives (without knowing the details of their preparation or the people engaged therein), including the Polish Legation’s encryption officer Stanisław Nahlik[14] and the delegate of the Polish Minister of Labor and Social Policy Stanisław Jurkiewicz.[15] Also, a few representatives of the Jewish community had some knowledge of the operation. Worthy of note among them were Isaac Sternbuch,[16] who in November 1943 took the place of the recently deceased Chaim Eiss[17] in the rescue operations that were then being carried out. Silberschein’s aides Alfred Szwarcbaum,[18] Nathan Schwalb,[19] and Nathan Eck[20] were also significant. Their tasks included the distribution of passports in the ghettos and the gathering of personal data for would-be recipients. These people might be referred to as the Ładoś group’s “second circle”. They knew about the passports and who to approach in order to obtain them, but there is no evidence that they fully understood the mechanisms which lead to their creation. It is also questionable how far Fanny Hirsch, a secretary who married Abraham Silberschein in 1944, was apprised of the operation. Although she was aware of the passport issue, her lack of knowledge of the role of the Polish diplomats in their production suggests that her husband did not keep her fully informed.[21]

There was also a “third circle” of those who had certain knowledge about the operation: those who received, hid and smuggled the passports without knowing where they had come from or how they had been prepared. This group includes several dozen Jewish and non-Jewish Swiss residents who were aware of the possibility of arranging documents for their friends and relatives and took the risk to acquire them and finance the operation.[22] It also includes members of the Polish and Dutch resistance movements[23] as well as certain individuals who were rescuing Jews in occupied Europe. It was to their addresses that the passports were sent and it was with their help that they reached the beneficiaries.[24] There were also staff members in Poland’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs who led a partly successful campaign to have the documents recognized.[25] The “fourth circle”, then, includes the passport recipients themselves, who had actively applied for a document and then shared their limited knowledge of the procedure with their fellows. Traces of these rumors are often found in memoirs and in post-war testimonies.[26]

By May 1943, the Polish government was aware that in Bern a large operation of forging passports and other documents was taking place and supported it “out of purely humanitarian reasons.”[27] Aleksander Ładoś was asked to send a list of the names of the recipients in order for effective intervention to be carried out so that the governments of those countries could be persuaded to recognize their “false” citizens. Ładoś, likely mistrustful of the secrecy of the Polish ciphers, did not accede to the request for fear of being exposed. The only list—sent by Abraham Silberschein in 1944—is incomplete.[28]

Footnotes

[1] J. Kumoch, Grupa Berneńska – dyplomaci Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z pomocą Żydom. Wystąpienie ambasadora RP w Szwajcarii, dr. Jakuba Kumocha, wygłoszone 4 lutego 2018 r. w Muzeum Pamięci Shoah w Paryżu, “Polski Przegląd Dyplomatyczny” 2018, no. 2, pp. 146–171.

[2] M. Wallace, In the Name of Humanity. The Secret Deal to End the Holocaust, Toronto 2018, p. 99; D. Kranzler, The Man Who Stopped the Trains to Auschwitz. George Mantello, El Salvador, and Switzerland’s Finest Hour, Syracuse 2000, pp. 28–34; G. Martínez Espinosa, Pasaporte a la vida. La Callada Historia de un Cuencano, Cuenca 2011, p. 136; D. Dorfzaun, Las Corrientes de Resistencia de Apoyo a los Judíos en Contra del Nazismo: El Caso del Cónsul Manuel Antonio Muñoz Borrero, Quito 2008–2009; Archives of Modern Records (hereafter: AAN), file no. 2/495/0/325, Poselstwo RP w Bernie, Depesze Poselstwa RP w Bernie do Ministerstwa Spraw Zagranicznych w Londynie. Książka korespondencji szyfrowej: Depesza nr 91 z 10.06.1941 r. [Telegrams from the Polish Legation in Bern to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in London. Book of coded correspondence: telegram no. 91 dated 10.06.1941], information on the issuing of passports in Italy with the aid of the Chilean Embassy.

[3] In the 1940s, there were very few diplomatic institutions in the world that functioned at the highest level of representation, i.e., at the level of an embassy with an ambassador at its head. Usually, as was the case in both Poland and Switzerland, bilateral diplomatic relations were maintained by lower-ranked Legation staff who were directed by an envoy (the Polish Legation in Switzerland was elevated to the rank of embassy during the Polish People’s Republic in 1958). It must also be noted that German pressure resulted in the Swiss authorities’ refusal to recognize Aleksander Ładoś’ diplomatic rank, as a result of which he formally served as the head of the Polish Legation (chargé d’affaires) throughout the entire period of his work in the years 1940–1945. Internally, however, Ładoś was considered a fully authorized envoy and his nomination to the position bears the signatures of Poland’s erstwhile President, Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs, see Swiss Federal Archives, file no. E2001E#1000/1571#477*, ref. B.22.21477, Lados, Aleksander, Ex-Chargé d’Affaires, 1940–1950, Dossier; Central Military Archives (hereafter: CAW), file no. WBBH IX.1.2.19, Pamiętniki A. Ładosia, vol. II, pp. 146–166; Documents Diplomatiques Suisses 1848–1945, vol. 13, pp. 653–657.

[4] Aleksander Ładoś (1891–1963) was the Polish envoy to Latvia (1923–1926), Consul General in Munich (1927–1931) and Minister without Portfolio in Gen. Władysław Sikorski’s government in exile (1939–1940). He played the central role in the passport campaign, authorizing and overseeing the work of his diplomats and surrounding his subordinates with complete diplomatic and political support which included intervention and coming to their defense when the operation was discovered by the Swiss authorities. Thanks to his determination, Swiss officers suspended their investigation into the Polish and Jewish participants in the campaign in fall 1943. At the end of that year, Ładoś began to intervene diplomatically, after which the Polish government in exile—supported by both the USA and the Vatican—was able to convince Paraguay to temporarily recognize the forged passports. Moreover, Ładoś made it possible for Jewish organizations to make use of Poland’s diplomatic ciphers in order for them to remain in constant contact with the USA and, towards the end of the war, to inform them of the on-going negotiations regarding the evacuation of Jews still being held by the German occupier. Ładoś died in Poland shortly after his return from France, leaving unpublished memoirs behind.

[5] J. Friedenson, D. Kranzler, The Heroine of Rescue: The Incredible Story of Recha Sternbuch, New York 1984, p. 58; J. Fridenzon, Chasidei Umot HaOlam, “Dos Yidishe Vort” 1982, no. 230, p. 45.

[6] Stefan Jan Ryniewicz (1903–1988) was the deputy head of the Polish Legation in Bern in the years 1938–1945 and simultaneously the formal head of the Consular Section. He was one of the initiators of the passport campaign. His duties included convincing RELICO to become involved in the operation, arranging conditions conducive to its continuation (keeping contact with Jewish organizations, the consuls of the USA and Latin American nations, the remaining diplomatic corps in Bern and with the federal authorities in Switzerland). Ryniewicz—the former Consul in Bern and Riga and the highest-ranked professional diplomat in the Legation—was attributed to several cases in which he was personally involved in both the filling out of Paraguayan passports and in the transport of the documents between consulates. Following the end of the war, Stefan Ryniewicz settled in Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he was a well-known member of the Polish diaspora. He was awarded the Order of Polonia Restituta by the president of Poland’s government in exile in 1972, see Swiss Federal Archives, file no. E2200.79-01#1970/171#473*, ref. A.II.53, Hügli Rudolf, Consul du Paraguay à Berne, 1943–1943, Dossier; Swiss Federal Archives, file no. E4800.1#1967/111#328*, Beziehungen zu anderen Staaten, 1934–1956, Dossier, Notice du Chef de la Division de Police du Département de Justice et Police, H. Rothmund, 06.09.1943; AAN, file no. 2/495/0/-/404/4-5, Poselstwo RP w Bernie, List Stefana Ryniewicza do Abrahama Silberscheina z 23.08.1943 r [Letter from Stefan Ryniewicz to Abraham Silberschein dated 23.08.1943]; Dziennik Urzędowy Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej nr 8, London, 31.12.1972.

[7] Konstanty Rokicki (1899–1958) was a reserve cavalry officer, Consul in Minsk, Riga and Cairo. De facto head of the Consular Section of the Polish Legation in Bern in the years 1939–1945, he was engaged in the process of issuing forged Latin American passports from the operation’s outset. Between 1941 and 1943, he personally filled out over a thousand Paraguayan passports by hand, entering the personal data of Jews residing in European nations under German occupation. The information necessary for the documents to be issued was delivered to him by Abraham Silberschein and Chaim Eiss, members of Jewish organizations present in Switzerland (RELICO and Agudat Yisrael respectively). Rokicki refused to return to Poland after the war and remained in Switzerland. Living in the cantons of Bern, Zug and Uri, he gradually fell into greater and greater destitution. He died, forgotten, in Lucerne in 1958. His grave was restored in 2018. According to Russian sources, Rokicki was an officer of Polish military intelligence and was one of its aces in the Soviet Union, see Swiss Federal Archives, file no. E2001E#1000/1571#483*, ref. B.22.21, Rokicki, Konstanty, Attaché, 1939–1946, Dossier; CAW, file no. KW 101/R-848, Kolekcja akt personalnych i odznaczeniowych; CAW, file no., AP-6764, Akta personalne Konstantego Rokickiego; Flüelen Almshouse Archives, Protokoll Armustrat Flüelen dated 30.08.1957 and 18.10.1957, copy in the author’s collection (private archives of the Polish Embassy in Bern); Flüelen Almshouse Archives, Flüelen Almhouse Chronicle dated 1957 and 1958, copy in the author’s collection (private archives of the Polish Embassy in Bern); Ł. Ulatowski, Niezbrzycki – wybrane aspekty biografii wywiadowczej kierownika Referatu „Wschód”, from: http://www.historycy.org/index.php?act=Attach&type=post&id=16066 [access: 02.08.2019], pp. 14–15, 19; O. Cherenin, Ocherki agenturnoy bor´by: Konigsberg, Dantsig, Berlin, Varshava, Parizh. 1920–1930e gody, Kaliningrad 2014.

[8] Dr Juliusz Kühl (1913–1985) came from a Hassidic Jewish family. Although he began his diplomatic career as an expert in the field of humanitarian aid for Polish refugees, it was shortly after his employment at the Polish Legation in Bern (1940) that he became the informal advisor on Jewish issues to the head of the Legation, Aleksander Ładoś. Kühl played a significant role in maintaining strict cooperation between the Legation and the Jewish diaspora in Switzerland as well as in bribing the consuls of Latin American countries with accreditations in Bern and transporting the passports and certificates purchased from them. After the war, Kühl emigrated first to Canada and then to the USA, where he made his living as a successful businessman and was a respected member of the Jewish community, see M. Mackinnon, “He should be as well known as Schindler”: Documents reveal Canadian citizen Julius Kuhl as Holocaust hero, “The Globe and Mail” 07.08.2017.

[9] Abraham Silberschein (1882–1951) was a founder of the Committee for Relief of the War-Stricken Jewish Population (RELICO). He arrived in Switzerland three weeks before the outbreak of the Second World War as a delegate to the World Zionist Organization. As a known and influential personality (he was formerly a member of the lower house of Poland’s parliament in the 1922–1927 term, as well as a well-known lawyer in Lwów and a representative of the WJC), he played an important role in gathering and passing on data for the Latin American passports to the Polish diplomats and in organizing the financial base for the whole operation. As much as he differed politically from Chaim Eiss, a representative of the Agudat Yisrael movement, the two worked closely together to create lists of people for whom the documents were to be issued. After the war, he remained in Geneva, where he died.

[10] Chaim Eiss (1876–1943) emigrated to Switzerland at the start of the 20th century. He was one of the founders of the Orthodox Agudat Yisrael movement in 1912 and was its main representative in Switzerland during the Second World War. Like Abraham Silberschein, Eiss played an important role both in providing the Polish diplomats with the personal data required to fill out the Latin American passports, as well as in securing the necessary funding. It is estimated that the list of names he recorded amounts to several thousand people who may have been included in the passport campaign. Eiss died in Zurich in fall 1943. He was involved in the Polish Legation's passport operation until his final moments, see Archives of the Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chaim Eiss collection.

[11] Swiss Federal Archives, file no. E4320B#1990/266#2164*, ref. C.16-02032, Silberschein, Adolf, 1882, 1940–1956, Dossier, Audition de Abraham Silberschein: de 1er Septembre 1943; Swiss Federal Archives, file no. B23.22.Parag-OV, Huegli, Rudolf, Honorarkonsul, Bern, 1929–1944, Dossier, Verantwortlichkeit einzelner Beamten der Polnischen Gesandschaft in der Passfälschungesache Hügli, 09.08.1943; Yad Vashem Archives (hereafter: YVA), file no. M.20/64, Archive of Dr. Abraham Silberschein, Geneva: Documentation regarding relief to persecuted Jews, 1939–1951 (hereafter: Archive of Dr. Abraham Silberschein), Correspondence with the Polish Legation in Switzerland regarding the issuing of passports to Polish citizens, help to Polish refugees and POWs, sending parcels to Poland and transmitting information, Testimonies of J. Kühl dated 23.05.1944 and correspondence kept between group members; YVA, file no. M.20/168, Archive of Dr. Abraham Silberschein, Correspondence with personnel in the Haiti Consulate and with the Polish Consul in Bern regarding preparation of consular letters and protective passports; also: Archives of the Memorial and Museum Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chaim Eiss collection.

[12] CAW, file no. WBBH IX.1.2.20, Pamiętniki A. Ładosia, vol. III, p. 7. Translated fragment from Ładoś' memoirs pictured on the opposite page: “[Cooperation] was worse with the third Department with which I had much to do regarding the civilian refugees, escapees from German POW camps, deportees for forced labor, and especially the Jewish issues to which I will return in another section. This was the Department of Justice and Police, and these issues were the concern of the police branch, and more specifically of the unit charged with policing foreigners, the Fremdenpolizei.”

[13] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (hereafter: USHMM), file no. RG-27.001, Julius Kühl collection, Untitled memoirs of Juliusz Kühl.

[14] Stanisław Nahlik (1911–1991) was an attaché at the Polish Legation in Bern during the Second World War and also fulfilled the roles of the Legation’s paymaster and encryption officer due to staff shortages. It should be noted that Nahlik, who was merely at the start of his career, possessed limited knowledge regarding the creation of the documents, did not understand Juliusz Kühl’s role and likely had no knowledge of the duties of Konstanty Rokicki and the other diplomats, see AAN, file no. 2/495/0/-/327, Poselstwo RP w Bernie, Depesza Stanisława Nahlika „Dla Wagnera” nr 257 z 30.06.1943 r. [Telegram from Stanisław Nahlik “To Wagner” no. 257 dated 30.06.1943], p. 149; Archives of the Institute of National Remembrance in Kraków (hereafter: AIPN Kr), file no. Kr 009/9167, Teczka personalna Stanisława Nahlika; S. E. Nahlik, Przesiane przez pamięć, vol. III, Kraków 2002, pp. 286–287.

[15] YVA, file no. M.20/64, Archive of Dr. Abraham Silberschein, Correspondence with the Polish Legation in Switzerland regarding the issuing of passports to Polish citizens, help to Polish refugees and POWs, sending parcels to Poland and transmitting information, pp. 219–221.

[16] Isaac (Yitzhak) Sternbuch came from a well-known Orthodox Jewish family and was the Swiss representative of the Vaad HaHatzalah committee. He and his wife, Recha Sternbuch née Rottenberg (1905–1971), helped Jewish refugees in Switzerland, including those who had made their way there illegally from France. The Sternbuchs headed the Hilfsverein für jüdische Flüchtlinge im Shanghai organization which was founded in 1941, the main aim of which was to help the rabbis and students of yeshivas who had reached Shanghai. They went on to expand their operation and changed the name of the organization to Hilfsverein für jüdische Flüchtlinge im Ausland. They sent packages to Jews in Poland and Czechoslovakia, took part in rescue campaigns through the use of South American passports and maintained contact with the leaders of Jewish organizations in Slovakia and Hungary.

[17] AAN, file no. 2/495/0/-/330, Poselstwo RP w Bernie, Depesza Poselstwa RP w Bernie do Ambasady RP w Waszyngtonie nr 32 z 18.11.1943 r. [Telegram from the Polish Legation in Bern to the Polish Embassy in Washington no. 32 dated 18.11.1943], p. 190.

[18] Alfred (Alf) Szwarcbaum (Schwarzbaum) (1896–1990) was born in Sosnowiec but moved from there to Będzin where he became an entrepreneur and started a family. He obtained a visa to Switzerland via his contacts and left Poland in April 1940 to settle in Lausanne. Szwarcbaum soon began to send food, clothes, money and papers to Poland. He was able to straddle the often uncoordinated Jewish and Zionist organizations located in Switzerland and obtain financial aid for Jews in Poland. He sent hundreds of packages to places under German occupation via Portugal, Sweden and Turkey. He visited refugee camps in Switzerland and corresponded with people living under German occupation. He also provided them with forged passports, which attracted the disapproving attention of the Swiss authorities, these fearing a violation of the country’s policy of neutrality. He emigrated to Palestine in 1946. He supported several foundations in Israel and financed scholarships for students. Inquiries about him were made at the Massuah Museum in Tel Yitzhak (http://www.infocenters.co.il/massuah/list.asp), Beit Lohamei HaGhetaot (http://infocenters.co.il/gfh), Yad Vashem in Jerusalem (https://documents.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=en), the federal archives in Bern (https://www.swiss-archives.ch/volltextsuche.aspx) and at the Archiv für Zeitgeschichte in Zurich (http://onlinearchives.ethz.ch), Archives of the Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw (https://www.jhi.pl, AŻIH, sygn. 301/5500, Szwarcbaum Alf).

[19] Nathan Schwalb (1908–2004) was a trade unionist and member of the Zionist organizations HeHalutz and Histadrut. He emigrated to Palestine in 1929, where he became a member and one of the leaders of the Hulda kibbutz. As a delegate of HeHalutz in Prague and Vienna in 1938–1939, he acquired certificates for European Jews and enabled them to emigrate to Palestine. In August 1939, he took part in the 21st and final pre-war Zionist Congress in Geneva. Following the outbreak of the Second World War, Schwalb set up the world center of the HeHalutz organization in Geneva. He corresponded with hundreds of people in occupied countries, sent packages via the Red Cross—particularly to Poland—and organized financial support. He also aided Jewish refugees in Switzerland. Schwalb returned to the Hulda kibbutz in Palestine after the war and was one of its leading members. From 1946 on, he became Histadrut’s delegate in contact with workers’ organizations in Europe, see YVA, file no. M.20/86, Archive of Dr. Abraham Silberschein, Correspondence of Nathan Schwalb, head of the HeHalutz movement in Geneva, regarding lending aid to members of the pioneer youth movements in countries occupied by Germany.

[20] Nathan (Natan) Eck (Eckron) (1889 or 1896–1982) was a journalist, education activist, doctor of law, member of the Gordonia youth organization and a Histadrut party activist. He lived in Łódź during the interwar period, where he worked as a journalist. After the outbreak of the Second World War, he escaped to Warsaw in November 1939 to avoid being captured by the Gestapo. He was the director of the underground Tarbut high school in the Warsaw Ghetto, an activist for the Tkuma organization, an employee at Jewish Social Self-Help and also edited Gordonia’s conspiratorial newsletter “Słowo Młodych”. On 20 August 1942, during the Grossaktion Warschau operation to deport Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto, he escaped with his family to Częstochowa and then successfully crossed the border and reached Będzin. In March 1943, Eck received a Paraguayan passport and wanted to leave Poland under the auspices of being a foreign citizen, but he was transferred to the Tittmoning camp in Germany and then to the Vittel camp in France. He was deported to Auschwitz in May 1944. He escaped from the transport and made his way to Paris where he lived in hiding until the end of the war. He emigrated to Israel in 1948. He was one of the founders of the Yad Vashem Institute, the first editor of “Yad Vashem Studies”, and also a Holocaust researcher. His memoirs were published under the title ha-To’im be-darkhe ha-mavet: havai v.e-hagot bi-yeme ha-kilayon, Jerusalem, 1960, see YVA, file no. P.22/22, Nathan Eck Collection Documentation regarding Jewish emigration, travel documents and HICEM activities (hereafter: Nathan Eck Collection).

[21] Swiss Federal Archives, file no. E4320B#1990/266#2164*, ref. C.16-02032, Silberschein, Adolf, 1882, 1940–1956, Dossier, Audition de Fanny Hirsch: de 1er Septembre 1943; N. Eck, The Rescue of Jews with the Aid of Passports and Citizenship Papers of Latin American States, “Yad Vashem Studies” 1957, vol. 1, pp. 125–152. In this latter work, Eck references an exchange of correspondence with Fanny Hirsch the contents of which nevertheless lacks information on the roles of the Polish Legation in Bern and of Konstanty Rokicki who personally forged the Paraguayan documents.

[22] YVA, file no. M.20/179, Archive of Dr. Abraham Silberschein, File cards with personal information regarding 1522 people from Krakow, Buczacz, Amsterdam, Warsaw, Bedzin, Sosnowiec, Drohobycz, Przemysl and other places, to whom rescue certificates from Honduras and Paraguay were sent, pp. 15–30.

[23] The finding of four passports belonging to Dutch airmen, which enabled them as non-Jews to reach Great Britain, suggests links between the Dutch resistance movement and the Ładoś group. Similar links with the Polish resistance movement might also have been alluded to, for example in the words of Stanisław Zalewski, who claimed that he and his brother smuggled “South American passports”, Relacja Stanisława Zalewskiego, Warszawa, 23.03.2018 r., available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DRNZILUo7Ng [access: 02.08.2019].

[24] YVA, file no. M.20/179, Archive of Dr. Abraham Silberschein, File cards with personal information regarding 1522 people from Krakow, Buczacz, Amsterdam, Warsaw, Bedzin, Sosnowiec, Drohobycz, Przemysl and other places, to whom rescue certificates from Honduras and Paraguay were sent, item 305, Document for Józef Grynblatt and his wife sent to the address of Waleria Malaczewska, a member of “Żegota”.

[25] AAN, file no. 2/495/0/-/322, Poselstwo RP w Bernie, Depesze MSZ w Londynie do Poselstwa RP w Bernie, Depesza MSZ RP w Londynie do Poselstwa RP w Bernie nr 629 z 31.12.1943 r. [Telegram from the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in London to the Polish Legation in Bern no. 629 dated 31.12.1943], p. 244.

[26] E.g. R. Zariz, Attempts at Rescue and Revolt – Attitude of Members of the Dror Youth Movement in Bedzin to Foreign Passports as Means of Rescue, “Yad Vashem Studies” 1990, vol. 20, pp. 211–236.

[27] AAN, file no. 2/495/0/-/404, Poselstwo RP w Bernie, Sprawy Paszportowe, Pismo nr 85 z 19.05.1943 r. [Passport Issues, Letter no. 85 dated 19.05.1943], sent via courier from the ministry of foreign affairs in London to the Polish Legation in Bern.

[28] AAN, file no. 800/42/0/-/616, Archiwum Instytutu Hoovera, Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych, Jews, fol. 24–29, Korespondencja Poselstwa RP w Bernie z MSZ RP w Londynie z 23.10.1944 r. [Correspondence between the Polish Legation in Bern and the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs in London dated 23.10.1944].

Development Methodology for the Lados List

The objective of this research was to recreate the most complete possible scope of the Ładoś group’s work and to reconstruct a list of people who, between 1941 and 1943,29 might have come into possession of one of the documents of Paraguay, Honduras, Haiti and Peru that were forged in Switzerland. It is also important to determine how many of those people survived the war, as such data would enable preliminary conclusions to be drawn as to the efficacy and scope of the rescue operation. […]

Summary

Over the course of several years of research, it has been possible to successfully identify 3,282 holders of passports and citizenship certificates of Paraguay, Honduras, Haiti and Peru, created through the illegal network known as the Ładoś group, which operated in neutral Switzerland during the Second World War and centered around the Polish Legation in Bern in cooperation with at least two Jewish organizations in Geneva and Zurich. The key person in this operation was the Polish envoy Aleksander Ładoś, who agreed for the operation to take place, strove to have the Swiss authorities tolerate it and also delegated and managed his staff’s tasks in its execution; the direct executors being three Polish diplomats (Stefan Ryniewicz, Konstanty Rokicki, and Juliusz Kühl) and two Jewish activists (Abraham Silberschein and Chaim Eiss). The role of Konstanty Rokicki was particularly visible as he was personally responsible for the creation of likely nearly half of all the documents produced.

[…]

For a list of visas issued by the Lados Group, see The Lados List - Visas